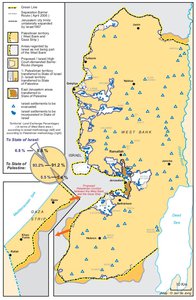

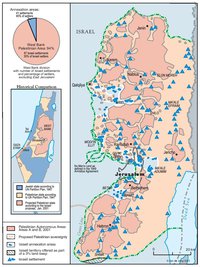

THE SHARON PROPOSAL, SPRING 2001

Map Details

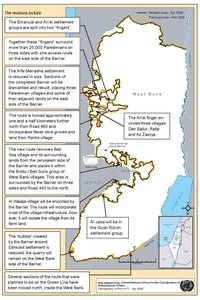

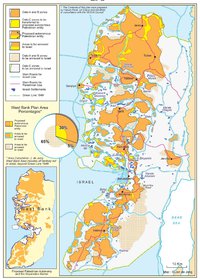

US President Clinton and Israeli Prime Minister Barak each made it clear that their respective successors, George Bush and Ariel Sharon, were free of prior negotiating positions and that Israel’s new ‘unity’ government was under no obligation to proceed with pre-election final status talks. Himself a hard-line settler and principal architect of much of Israel’s settlement program, Sharon had rejected withdrawal from the OPT during his election campaign and responded to the formula of land-for-peace with characteristic belligerence. Regarding any eventual evacuation of settlements, Sharon’s position was simple: “[A]s long as there is no peace we are there. And if in the future, with God’s help, there is peace, there will certainly be no reason for not being there.” Palestinian submission to Israeli settlement and land confiscation was, then, the primary prerequisite for the peace Sharon envisioned. Yet, the paradox between achieving real peace and pursuing settlement was far from lost on the new Prime Minister, who had earlier opined that, “[w]ere there not Jewish settlements today on the Golan Heights and Judea and Samaria, Israel would long ago have returned across the Green Line. If there is one source that prevented the agreement... and complicated... negotiations, it was [sic] only the Jewish settlements.” By May 2001, more than 500 Palestinians had been killed since the start of the Intifada (September 2000) and over 14,000 injured. Israeli losses totaled 82, 18 of these civilians inside Israel. That month, the report of the US-led Mitchell Committee of Inquiry (mandated in October 2000 to investigate the causes of violence) was published, calling on Israel to, “freeze all settlement activity, including the ‘natural growth,’” “lift closures,“ and, “ensure that security forces and settlers refrain from the destruction of homes and roads, as well as trees and other agricultural property.” The report demanded coordinated PA actions to “apprehend and incarcerate terrorists,” and urged both sides to return to and implement existing agreements. Sharon termed the call for a settlement freeze, “total madness,” and demanded a two-month period of ‘absolute quiet’ from the Palestinians before considering any “concessions.” The PA, on the other hand, accepted the Mitchell Committee’s recommendations in their entirety and called in vain on the US to oversee its implementation in full. In the meantime, with the conflict escalating daily into a series of reinvasions of PA areas, Sharon outlined the “concessions” he had in mind. Rejecting any return to outstanding commitments or final status talks, he proposed merely, “a non-belligerency agreement, for a lengthy and indefinite period, in an agreement that does not have a timetable, but a table of expectations.” His offer would, he suggested, “give them [the Palestinians] the necessary minimum,” by providing up to a 2% transfer of Area C, creating small connecting corridors between some existing A and B Area pockets. In all, the plan would grant the PA some unspecified form of control over 43% of the West Bank and leave the Gaza Strip unchanged. In the remaining 57% of the West Bank, Israeli settlements would “safeguard the cradle of the Jewish people’s birth and also provide strategic depth.” It is doubtful whether Sharon’s 43%-plan was ever more than a sop to those, internationally and locally, who found it easier to support his government’s military policies when they were coupled with a declared longterm ‘vision.’ The Prime Minister himself was under no illusions as to the likelihood of ending the Intifada through legitimizing confiscation and settlement at the expense of Palestinian statehood. The uprising had, from the outset, been directed precisely against these persistent traits in Israeli policy. One month into the Intifada, Fateh’s West Bank leader Marwan Barghouthi had explained: “We were calm for seven years in order to give a chance to negotiations... But the Israelis used that time in order to... continue their policy of a fait accompli on the ground: the new settlements, the expropriations, the confiscation of land... Why should calm now be restored? So that they can resume the same policy?” With its patently unacceptable and highly contingent “concessions” presented, Israel proceeded with its stepped-up military assault on PA territories and Palestinian population centers. By October, one year into the Intifada, 700 Palestinians had been killed (145 of them children), 384 homes demolished, nearly 400,000 trees uprooted and 25 new settlement ‘footholds’ established.8 As all hope of returning to peace talks was swept away, Israel’s Internal Security Minister Uzi Landau gave voice to the alternative vision of the government: “We must strike at them militarily and economically, at the prestige and authority and stability of the Palestinian Authority until it collapses.

Related Maps

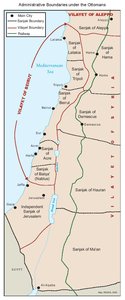

OTTOMAN PALESTINE, 1878

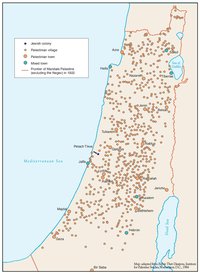

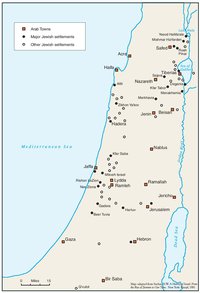

ARAB TOWNS AND JEWISH SETTLEMENTS IN PALESTINE, 1881-1914

THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT, 1916

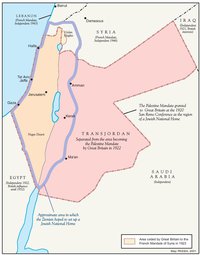

THE BEGINNING OF THE BRITISH MANDATE, 1920

PALESTINE UNDER THE BRITISH MANDATE

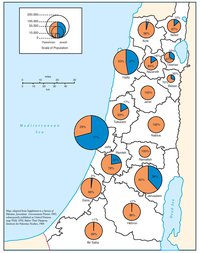

THE DEMOGRAPHY OF PALESTINE, 1931

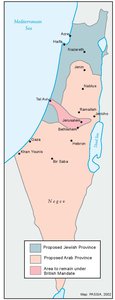

THE PEEL COMMISSION PARTITION PROPOSAL, 1937

THE WOODHEAD COMMISSION PARTITION PROPOSALS, 1938

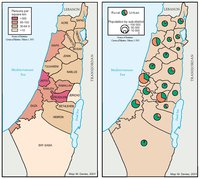

PALESTINIAN AND ZIONIST LANDOWNERSHIP BY SUB-DISTRICT, 1945

THE MORRISON-GRADY PARTITIONED TRUSTEESHIP PLAN, 1946

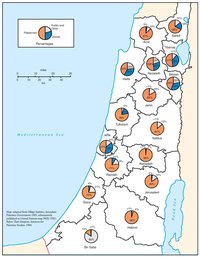

POPULATION OF PALESTINE BY SUB-DISTRICT, 1946

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE, 1948

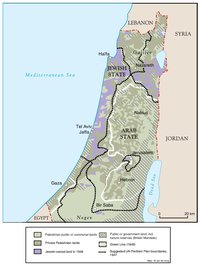

THE UNGA PARTITION PLAN, 1947 – THE 1948 WAR & THE 1949 ARMISTICE LINES

POPULATION MOVEMENTS, 1948-1951

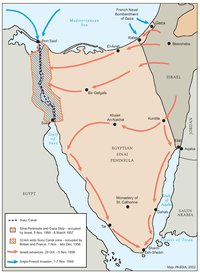

THE SUEZ WAR, 1956

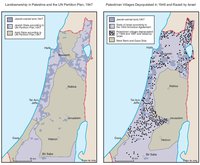

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE AND THE UN PARTITION PLAN - PALESTINIAN DEPOPULATED AND DESTROYED VILLAGES, 1948-1949

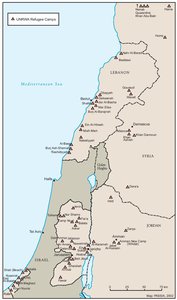

THE PALESTINIAN DIASPORA, 1958

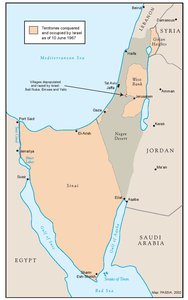

THE NEAR EAST AFTER THE JUNE 1967 WAR

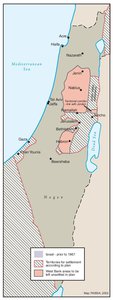

THE ALLON PLAN, JUNE 1967

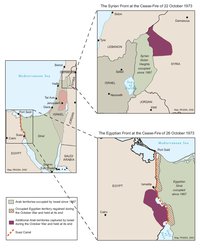

THE OCTOBER WAR, 1973

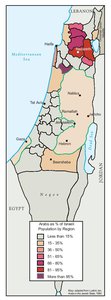

THE PALESTINIANS INSIDE ISRAEL, 1977

THE CAMP DAVID ACCORDS, 1978-1979

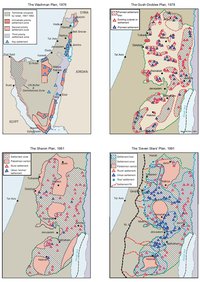

ISRAELI SETTLEMENT MASTER PLANS, 1976-1991

THE 1991 MADRID PEACE CONFERENCE & ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS

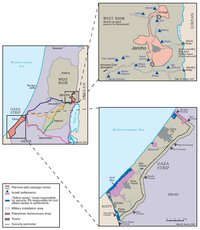

GAZA-JERICHO (OSLO I) AGREEMENT, CAIRO, 4 MAY 1994

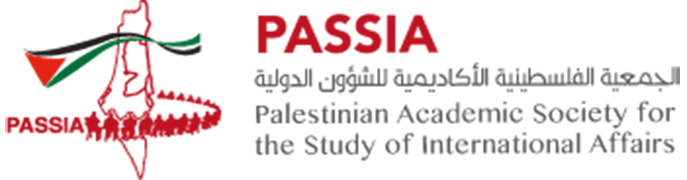

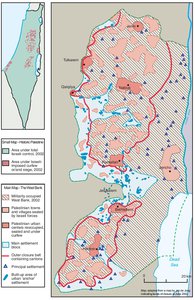

INTERIM (OSLO II) AGREEMENT, TABA, 28 SEPTEMBER 1995

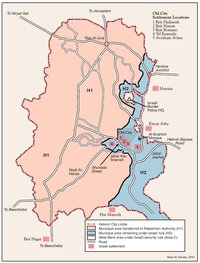

HEBRON PROTOCOL, 15 JANUARY 1997

WYE RIVER MEMORANDUM, 23 OCTOBER 1998

SHARM ESH-SHEIKH AGREEMENT, 4 SEPTEMBER 1999

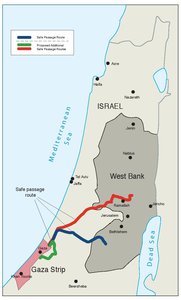

PROTOCOL CONCERNING SAFE PASSAGE BETWEEN THE WEST BANK AND THE GAZA STRIP, 5 OCTOBER 1999

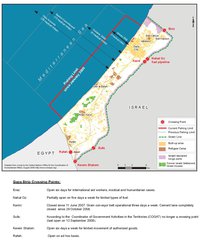

GAZA, 2000

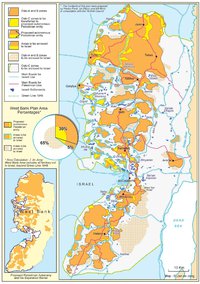

WEST BANK AND GAZA STRIP, MARCH 2000

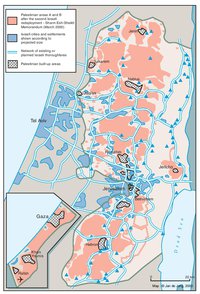

CAMP DAVID PROJECTION, JULY 2000

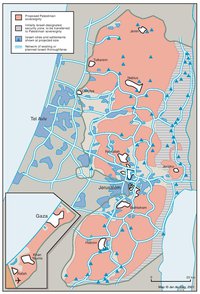

TABA TALKS PROJECTION, JANUARY 2001

THE REINVASION OF THE PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES, 2001-2002

THE ROAD MAP, 2003

THE GENEVA INITIATIVE AND ACCORD, 2003

THE ISRAELI DISENGAGEMENT PLAN, 2003-2005

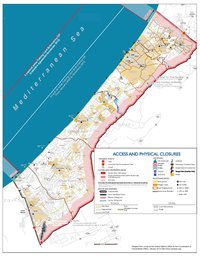

AGREED DOCUMENTS ON MOVEMENT AND ACCESS FROM AND TO GAZA, 2005

THE SETTLERS' PLAN FOR PALESTINIAN AUTONOMY, 2006

THE GAZA STRIP TODAY (2014)

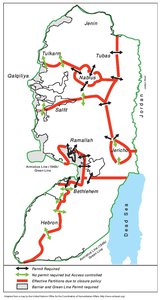

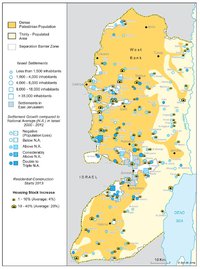

THE WEST BANK TODAY (2014)

ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES

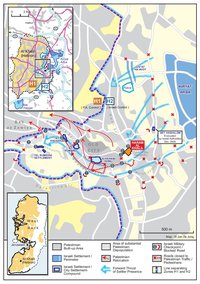

HEBRON

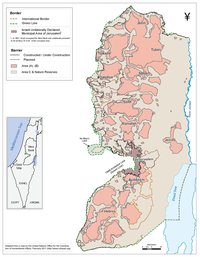

Area C