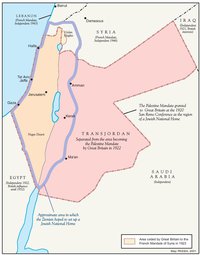

THE PEEL COMMISSION PARTITION PROPOSAL, 1937

Map Details

The 1929 Hope Simpson Commission of Inquiry had explicitly pointed to the incapacity of the economy and demography of Palestine to be further destabilized by Zionist immigration and settlement. Its recommendations were echoed by those of the 1930 Shaw Commission of Inquiry, named after Sir Walter Shaw, sent to investigate incidents of violence, which had peaked in a series of localized uprisings in 1929. The Shaw Commission stated that, “[a] continuation, or still more an acceleration, of a process which results in the creation of a large discontented and landless class is fraught with serious danger to the country.” The Commission urged the British government to urgently assess its immigration policy and to address the “meaning of the passages in the Mandate which purported to safeguard the interests of the non-Jewish communities.” The British ‘Passfield’ White Paper of October 1930 adopted these findings and ordered most land transfers frozen, while limiting immigration. However, Prime Minister McDonald, under pressure from Zionist leaders, revoked these clauses in February 1931 with the so-called ‘Black-Letter’, wherein he issued his personal assurances to WZO head Weizmann, going so far as to praise “the constructive work done by the Jewish people in Palestine [and their]... beneficial effects on the development and well-being of the country as a whole.” Unsurprisingly, the Palestinians were becoming increasingly frustrated with British policy, as the likelihood of their achieving their right to self-determination under the Mandate appeared to evaporate. In October 1933 nationwide strikes and demonstrations against Zionism and British collusion were met with force, leaving at least 12 Palestinians dead and fuelling outrage at Britain’s strong-arm tactics. By 1936, seven years after the Hope Simpson Commission, the Jewish population had risen by more than a further 150%, an additional 62 settlements had been created and nearly 1.5 million dunums of Palestinian land was the property of the Zionists. The Zionists saw the settlements as “[t]he guardians of Zionist land,” and recognized early on that “patterns of settlement would to a great extent determine the [future Jewish] country’s borders.” JA Executive Chairman, David Ben-Gurion, called the settlers, “the army of Zionist fulfillment.” In mid-April 1936, a series of Arab-Jewish clashes in the Jaffa area proved the inevitable trigger, as Palestinian National Committees sprang up across the country in support of a call for a general strike issued by the Palestinian representative leadership, the Arab Higher Committee (AHC). The AHC was banned soon after by the British, but despite the arrest of its leaders and the nationwide imposition of curfews, the uprising surged and from April 1936 until October the Arab Revolt swept Mandate Palestine.5 The extent of the revolt and its support throughout the region worried the British, who requisitioned additional troops in September to put down the uprising. Fearing domestic instability and under pressure from their British benefactor, regional Arab leaders eventually provided the necessary mediation to bring about a lull in the uprising, while Britain again dispatched an investigative commission. Arriving in November 1936, the Palestine Royal Commission, headed by Lord Peel, set out to assess the feasibility and future of the Mandate. Published in July 1937, the Peel Commission’s report concluded that, “the Mandate for Palestine should terminate and be replaced by a Treaty System...” The proposed treaty envisioned a partition of Palestine, with Jerusalem and Bethlehem retained under a separate Mandate, reaching to the port at Jaffa. The part allotted the Palestinians was to be united with Transjordan and the resulting Jewish state made to pay a subsidy to the Arab state, to which Palestinians within the area allotted the Jewish state would be compelled to move. The Peel Plan, with its twin premises of partition and ‘population transfer’, was to become the point of reference for most future schemes to solve the Palestine Question. The Palestinians flatly rejected the notion of a Zionist state on nearly 33% of Palestine and the dispossession of hundreds of thousands that this would entail. Encouraged by the legitimization it granted their program, but not content with the scale of conquest, the Zionist leadership accepted ‘in principle’ but rejected ‘in detail’ the partition plan, while Jabotinsky’s Revisionist movement rejected the idea outright and by September 1937 had commenced a violent campaign against Palestinians and the British, marking the resumption of violence and resurgence of the Arab Revolt.8

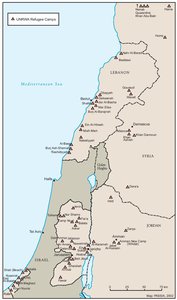

Related Maps

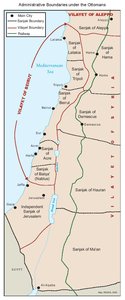

OTTOMAN PALESTINE, 1878

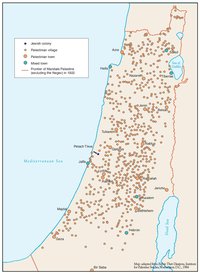

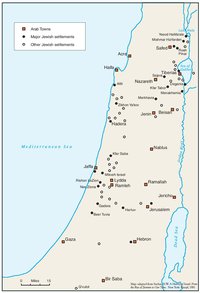

ARAB TOWNS AND JEWISH SETTLEMENTS IN PALESTINE, 1881-1914

THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT, 1916

THE BEGINNING OF THE BRITISH MANDATE, 1920

PALESTINE UNDER THE BRITISH MANDATE

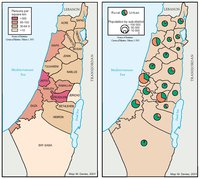

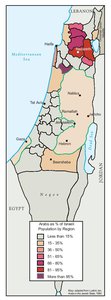

THE DEMOGRAPHY OF PALESTINE, 1931

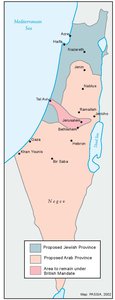

THE WOODHEAD COMMISSION PARTITION PROPOSALS, 1938

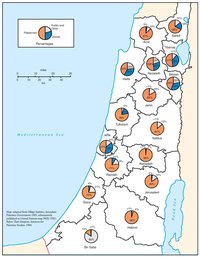

PALESTINIAN AND ZIONIST LANDOWNERSHIP BY SUB-DISTRICT, 1945

THE MORRISON-GRADY PARTITIONED TRUSTEESHIP PLAN, 1946

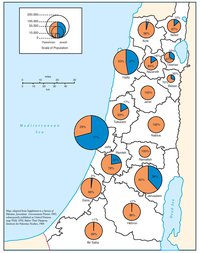

POPULATION OF PALESTINE BY SUB-DISTRICT, 1946

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE, 1948

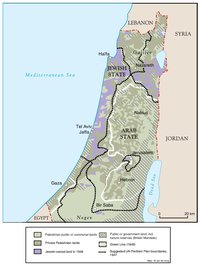

THE UNGA PARTITION PLAN, 1947 – THE 1948 WAR & THE 1949 ARMISTICE LINES

POPULATION MOVEMENTS, 1948-1951

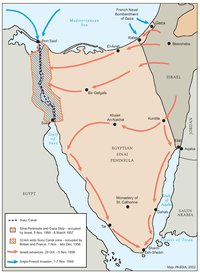

THE SUEZ WAR, 1956

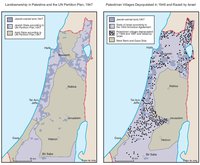

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE AND THE UN PARTITION PLAN - PALESTINIAN DEPOPULATED AND DESTROYED VILLAGES, 1948-1949

THE PALESTINIAN DIASPORA, 1958

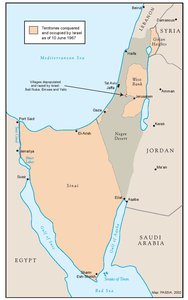

THE NEAR EAST AFTER THE JUNE 1967 WAR

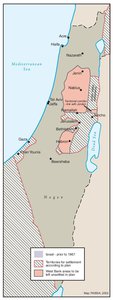

THE ALLON PLAN, JUNE 1967

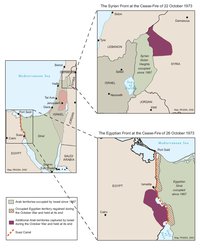

THE OCTOBER WAR, 1973

THE PALESTINIANS INSIDE ISRAEL, 1977

THE CAMP DAVID ACCORDS, 1978-1979

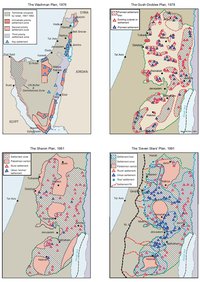

ISRAELI SETTLEMENT MASTER PLANS, 1976-1991

THE 1991 MADRID PEACE CONFERENCE & ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS

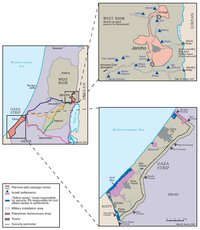

GAZA-JERICHO (OSLO I) AGREEMENT, CAIRO, 4 MAY 1994

INTERIM (OSLO II) AGREEMENT, TABA, 28 SEPTEMBER 1995

HEBRON PROTOCOL, 15 JANUARY 1997

WYE RIVER MEMORANDUM, 23 OCTOBER 1998

SHARM ESH-SHEIKH AGREEMENT, 4 SEPTEMBER 1999

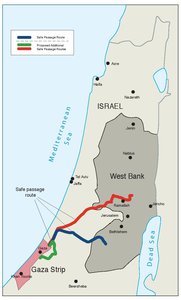

PROTOCOL CONCERNING SAFE PASSAGE BETWEEN THE WEST BANK AND THE GAZA STRIP, 5 OCTOBER 1999

GAZA, 2000

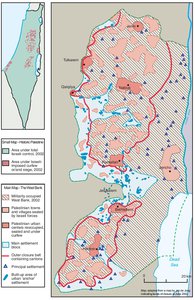

WEST BANK AND GAZA STRIP, MARCH 2000

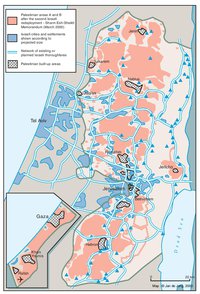

CAMP DAVID PROJECTION, JULY 2000

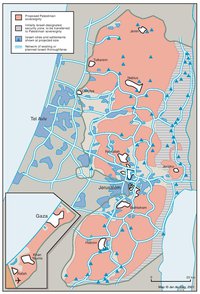

TABA TALKS PROJECTION, JANUARY 2001

THE SHARON PROPOSAL, SPRING 2001

THE REINVASION OF THE PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES, 2001-2002

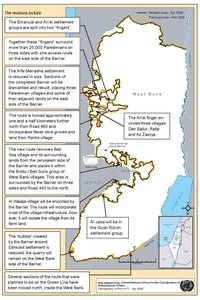

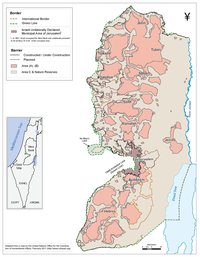

THE ROAD MAP, 2003

THE GENEVA INITIATIVE AND ACCORD, 2003

THE ISRAELI DISENGAGEMENT PLAN, 2003-2005

AGREED DOCUMENTS ON MOVEMENT AND ACCESS FROM AND TO GAZA, 2005

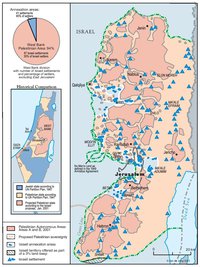

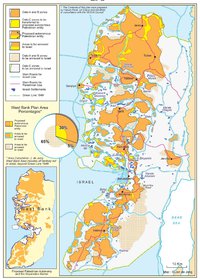

THE SETTLERS' PLAN FOR PALESTINIAN AUTONOMY, 2006

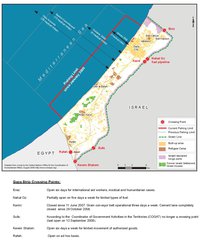

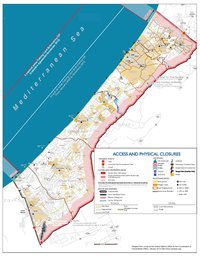

THE GAZA STRIP TODAY (2014)

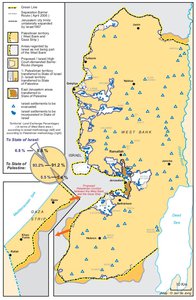

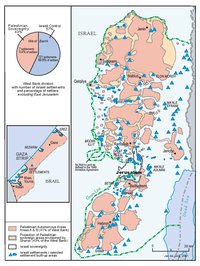

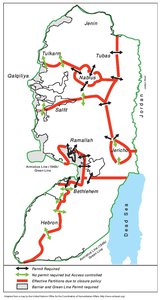

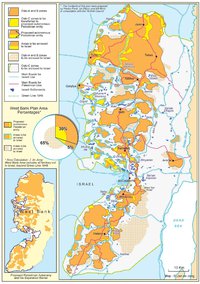

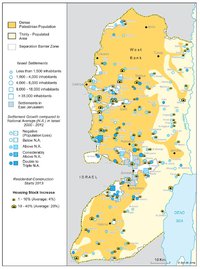

THE WEST BANK TODAY (2014)

ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES

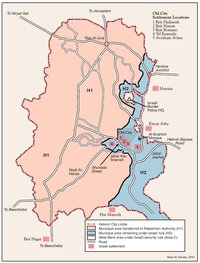

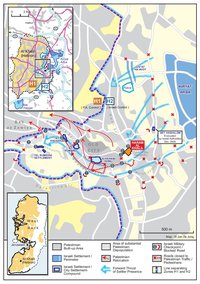

HEBRON

Area C