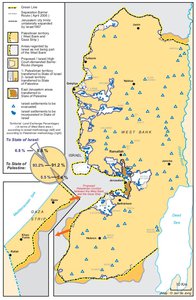

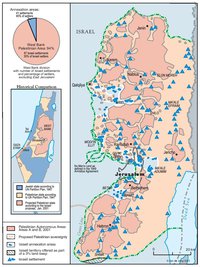

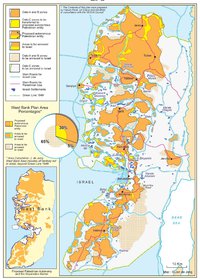

CAMP DAVID PROJECTION, JULY 2000

Map Details

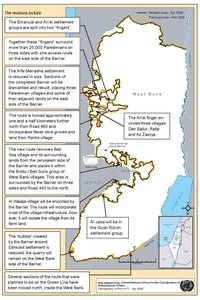

Final status talks did not begin in earnest until early 2000. May talks in Eilat were followed by meetings in Stockholm and then, in June, high-level talks convened in Washington. Thus, after seven years of renegotiating minor territorial transfers, a hasty dash was made for a final deal - now due by 13 September 2000. These talks finally broached the core issues of refugees, Jerusalem, settlements, water and borders. Rather than implement the third Oslo II redeployment, Barak opted to pin his precarious political existence on presenting the Israeli public with a final agreement before his Knesset coalition abandoned him. The erosion of his 73-seat (out of 120) majority began in September 1999 and by July 2000, he headed a divided Knesset minority, facing no-confidence motions. Thus, the likelihood of his securing the necessary Knesset majority to ratify any final deal negotiated with the PA was slim if existent and widespread Israeli public opposition to his policies cast a serious doubt over his credibility and that of his negotiating positions. Meanwhile, US President Clinton, hoping to crown his eight-year term (to end in January 2001) with a Middle East peace treaty, pressed the PA to drop its insistence on the overdue redeployment and joined Barak’s race against the political clock. Bent on achieving the breakthrough immediately, the US shunned Palestinian requests that progress be made in preparatory talks before any ‘make-or-break’ summit be held. In announcing the 11 July 2000 convening of the Camp David Summit, Clinton promised the reluctant PA that, should the talks fail, “there will be no finger-pointing.” A day before the summit, Barak lost a noconfidence motion in the Knesset and so arrived at Camp David set to face elections at home, which he would almost certainly lose without popular gains at the negotiating table. The summit lasted 14 days and ended without agreement. During the whole period, Barak met Arafat alone only once. Palestinian suffering in the interim period had been tempered by the prospect of the eventual implementation of UNSC Resolution 242 and a just solution to the refugee problem, as outlined at the Madrid Conference and in the DoP. At Camp David, Israel finally confirmed its unwillingness to abide by - or even approach - these principles. Israel’s ‘best offer’ soon transpired to be yet another annexation plan based on legitimizing its permanent sovereignty over 10-13.5% of the West Bank, and maintaining its settlement and security presence in a further 8.5-12% for an unspecified interim period. The remaining territory would be carved into at least three cantons, with settlement blocs, bypass roads and annexed Palestinian localities forming a barrier between the Nablus-Jenin area and Ramallah, and leaving Hebron and Bethlehem beyond an expanded Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty. The entire Jordan Rift would be retained for an unspecified ‘interim’ period and a corridor connecting the Hebron settlements would slice the Hebron canton in two from the south.6 Virtually all settlers were to remain and territorial provision was made for vast settlement expansion. Israel refused to accept any responsibility for the refugee problem, suggesting an international fund be established to equally compensate both them and Jewish immigrants to Israel of the same period (thus perpetuating the ‘population-swap’ myth). Through the annexation of settlement blocs, Israel stood to legitimize its control over the major West Bank water resources; airspace was to remain in Israeli hands; the bifurcated Palestinian state was to be strictly demilitarized and Israel was to retain full control over all borders. In Jerusalem, Barak’s ‘offer’ left the Palestinians with a cluster of sovereign pockets in the outer suburbs amidst a hugely expanded Israeli ‘Greater Jerusalem.’ The Old City, with its holy places, was to be under Israeli sovereignty and Palestinians granted “local safe-passage” to Al-Haram Ash-Sharif. In sum, nine years on from Madrid and the birth of the ‘land-for-peace’ process, Israel responded to the delayed crucial issues with an unequivocal, ‘No’ to refugees; ‘No’ to Jerusalem; ‘No’ to a return to 1967 borders; ‘No’ to removing Illegal settlements; and ‘No’ to Palestinian rights over natural resources. The offer, clearly unacceptable as it stood, was offered as a ‘now-or-never’ maximum by an Israeli Prime Minister who lacked domestic credibility and had already reneged on his Sharm Esh-Sheikh commitments. For Arafat the offer represented, “less than a Bantustan,” but the PA pleaded with Clinton to remain true to his “no fingerpointing” pledge and persuade Barak to consider the Camp David ideas a ‘taboo-breaking’ first in an ongoing process. But neither Clinton nor Barak stood to gain from inconclusive deals. As talks ended, on 25 July, Barak declared the Camp David positions “null and void,” and Clinton, at Barak’s request, not only openly blamed Arafat for the failure, but went on Israeli TV to praise Barak’s ‘vision and courage’. “In light of what has happened,” Clinton promised to move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. The Palestinians were deeply disappointed by the US-Israeli tactics and relieved that their leadership had withstood the pressure after succumbing so frequently in the past. Arafat came home to a hero’s welcome, as Barak announced a “time-out” from the peace process.

Related Maps

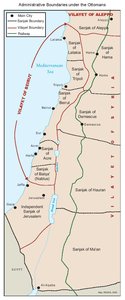

OTTOMAN PALESTINE, 1878

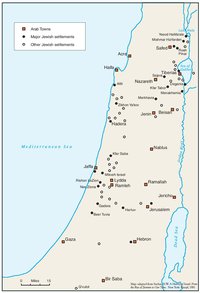

ARAB TOWNS AND JEWISH SETTLEMENTS IN PALESTINE, 1881-1914

THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT, 1916

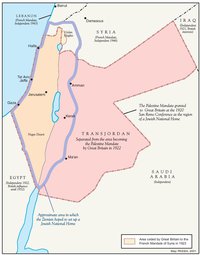

THE BEGINNING OF THE BRITISH MANDATE, 1920

PALESTINE UNDER THE BRITISH MANDATE

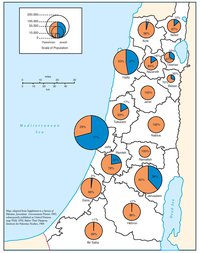

THE DEMOGRAPHY OF PALESTINE, 1931

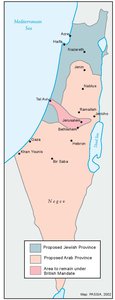

THE PEEL COMMISSION PARTITION PROPOSAL, 1937

THE WOODHEAD COMMISSION PARTITION PROPOSALS, 1938

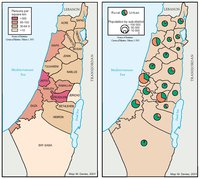

PALESTINIAN AND ZIONIST LANDOWNERSHIP BY SUB-DISTRICT, 1945

THE MORRISON-GRADY PARTITIONED TRUSTEESHIP PLAN, 1946

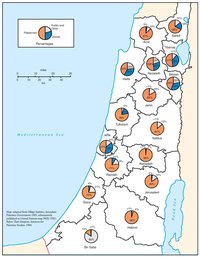

POPULATION OF PALESTINE BY SUB-DISTRICT, 1946

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE, 1948

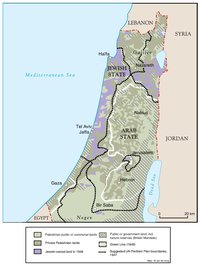

THE UNGA PARTITION PLAN, 1947 – THE 1948 WAR & THE 1949 ARMISTICE LINES

POPULATION MOVEMENTS, 1948-1951

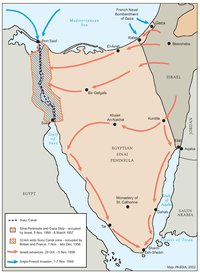

THE SUEZ WAR, 1956

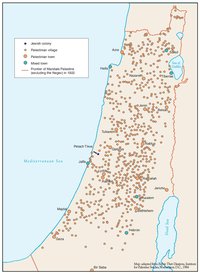

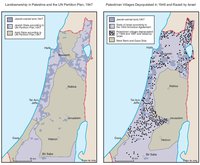

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE AND THE UN PARTITION PLAN - PALESTINIAN DEPOPULATED AND DESTROYED VILLAGES, 1948-1949

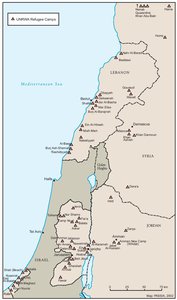

THE PALESTINIAN DIASPORA, 1958

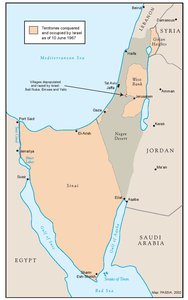

THE NEAR EAST AFTER THE JUNE 1967 WAR

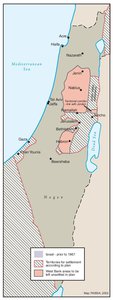

THE ALLON PLAN, JUNE 1967

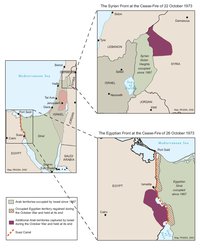

THE OCTOBER WAR, 1973

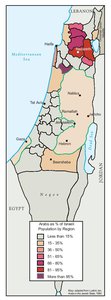

THE PALESTINIANS INSIDE ISRAEL, 1977

THE CAMP DAVID ACCORDS, 1978-1979

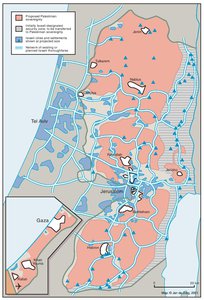

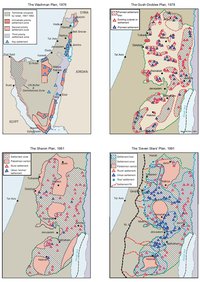

ISRAELI SETTLEMENT MASTER PLANS, 1976-1991

THE 1991 MADRID PEACE CONFERENCE & ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS

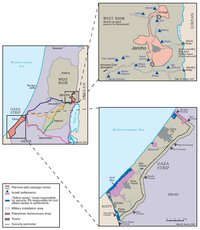

GAZA-JERICHO (OSLO I) AGREEMENT, CAIRO, 4 MAY 1994

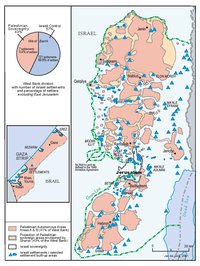

INTERIM (OSLO II) AGREEMENT, TABA, 28 SEPTEMBER 1995

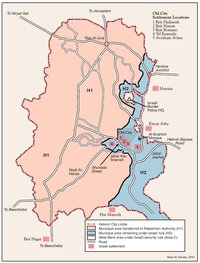

HEBRON PROTOCOL, 15 JANUARY 1997

WYE RIVER MEMORANDUM, 23 OCTOBER 1998

SHARM ESH-SHEIKH AGREEMENT, 4 SEPTEMBER 1999

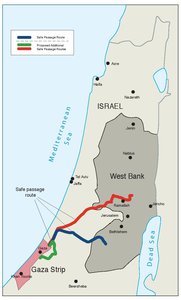

PROTOCOL CONCERNING SAFE PASSAGE BETWEEN THE WEST BANK AND THE GAZA STRIP, 5 OCTOBER 1999

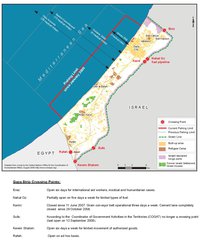

GAZA, 2000

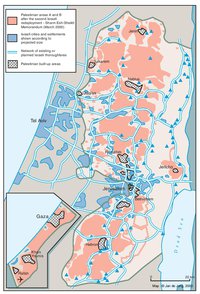

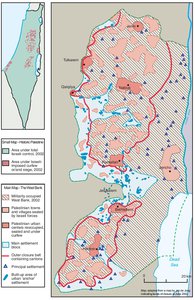

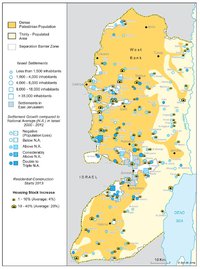

WEST BANK AND GAZA STRIP, MARCH 2000

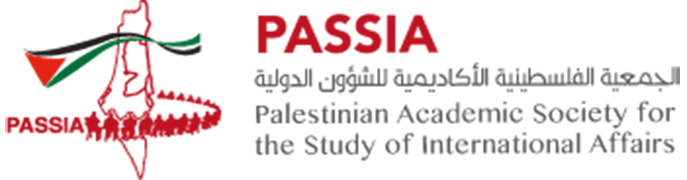

TABA TALKS PROJECTION, JANUARY 2001

THE SHARON PROPOSAL, SPRING 2001

THE REINVASION OF THE PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES, 2001-2002

THE ROAD MAP, 2003

THE GENEVA INITIATIVE AND ACCORD, 2003

THE ISRAELI DISENGAGEMENT PLAN, 2003-2005

AGREED DOCUMENTS ON MOVEMENT AND ACCESS FROM AND TO GAZA, 2005

THE SETTLERS' PLAN FOR PALESTINIAN AUTONOMY, 2006

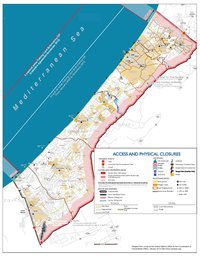

THE GAZA STRIP TODAY (2014)

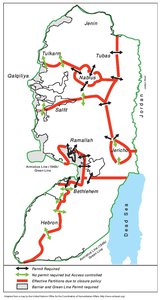

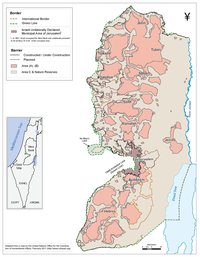

THE WEST BANK TODAY (2014)

ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES

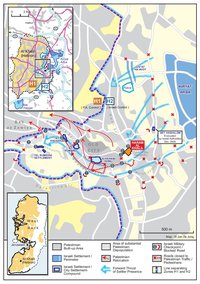

HEBRON

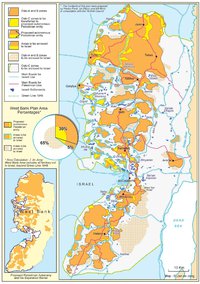

Area C