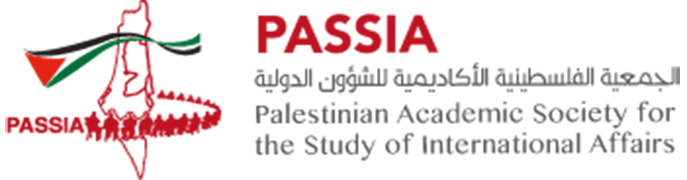

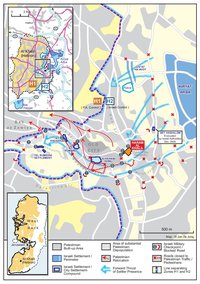

HEBRON PROTOCOL, 15 JANUARY 1997

Map Details

Fierce opposition to Oslo found Israel’s mainstream political ‘hawks’ (led by the Likud) sharing a rejectionist agenda with a range of fanatical movements. The right termed Rabin’s role in the peace process a betrayal and, in November 1995, a Tel Aviv law student shot the Prime Minister dead. As acting Prime Minister, Peres tried to temper his own association with Oslo. In January 1996, he ordered the assassination of Hamas activist Yahya Ayyash and in April launched an attack on Lebanon, striking a UN shelter at Qana', killing over 100 civilians. His brutal and counterproductive efforts left Israel facing international condemnation and a string of suicide attacks; they also saw the Arab-Israeli electorate turn its back on the Labor Party in the subsequent elections. On 29 May 1996, Likud leader Netanyahu was narrowly elected Prime Minister, ending the four-year political exile of Israel’s chief expansionists and casting doubt over the future of the peace process. The 28 March 1996 deadline set for Israel’s partial withdrawal from Hebron had been postponed until June by Peres, but the new government dismissed even this date, calling Oslo redeployments, “a conceptual mistake made by the previous government.” Hebron’s exclusion from 1995 redeployments was on account of some 450 radical messianic settlers, whose presence in the center of the Old City and ongoing seizure of Palestinian properties had long been a cause of friction. In February 1994, settler Baruch Goldstein had massacred 29 Palestinian worshippers in the Al-Ibrahimi Mosque. The Shamgar Commission of Inquiry noted the army’s role in the event and the Israeli public rejected the racist fanaticism of the settlers, yet the government resolved to blame and punish the Palestinian population: The mosque, closed to Muslims since the massacre, was divided to create a Jewish-only chamber and intensified military measures were imposed on the Palestinians so as to, “make it unnecessary for the Jews to carry weapons inside the tomb.” Netanyahu called the settlers, “the real pioneers of our day [who] deserve support and appreciation.” His victory brought Oslo to a standstill and only under US and UN pressure did he consent to even meet Arafat. Then, in late September 1996, he ordered the so-called Hasmonean Tunnel running beneath Jerusalem’s Al-Haram Ash-Sharif opened and sparked the clashes his security advisers had predicted. At least 80 Palestinians were killed in three days. The same month, Israel completed preparation of its ‘Field of Thorns’ operational plan for retaking PA territories. In October, President Clinton summoned King Hussein of Jordan, Arafat and Netanyahu to an emergency summit in an attempt to save the Oslo process. US assurances, and financial incentives, along with regional and domestic pressures triggered by a halt in the Oslo-linked process of ‘normalization’ with certain Arab states, eventually drew Netanyahu to the negotiating table. Guided by the provisions of the 1995 Oslo II Agreement, the resulting Hebron Protocol, signed on 15 January 1997, split the city into two zones: Palestinian - H1 (80% of the city) and Israeli - H2 (20%), which extended continued Israeli occupation to 20,000 Palestinians and the Al-Ibrahimi Mosque under the pretext of ‘securing’ the city’s five tiny settlement clusters. Ominously, the protocol saw the future of a city of 120,000 Palestinians defined by the illegal presence of 450 armed extremists. In exchange for this watered-down implementation of a long-overdue Israeli commitment, the PA was forced to accept Israel’s retreat from all its other prior agreements and place the size and timing of further redeployments at Israel’s discretion. Though Arafat obtained a non-binding ‘Note for the Record’ from the US promising unspecified redeployments within 15 months, Netanyahu had succeeded in arresting the process set in motion by the DoP. What little hope of ‘reciprocity’ and ‘mutuality’ that survived the Rabin era was extinguished with the Hebron Protocol, leaving the peace process dependent on Israeli unilateralism and international intervention. After concluding the agreement, Netanyahu told the Knesset his government had “inherited a difficult agreement,” that was now ”changed completely.” Pledging to “use the time interval in the agreement to achieve our goals,” Netanyahu ruled out any future Palestinian state and vowed to “maintain the unity of Jerusalem” and “insist on the right of Jews to settle in their land.” Six weeks later, Israel approved the vast new E1 settlement plan for East Jerusalem, commenced work on the controversial Har Homa settlement project on Jabal Abu Ghneim and unveiled a $16-million settlement ‘reinforcement’ program.

Related Maps

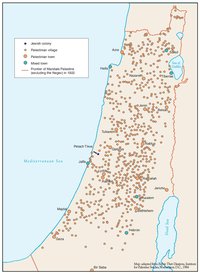

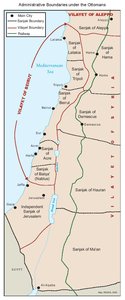

OTTOMAN PALESTINE, 1878

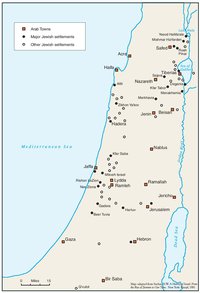

ARAB TOWNS AND JEWISH SETTLEMENTS IN PALESTINE, 1881-1914

THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT, 1916

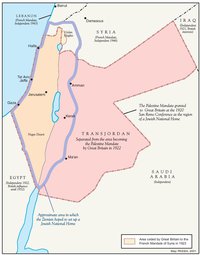

THE BEGINNING OF THE BRITISH MANDATE, 1920

PALESTINE UNDER THE BRITISH MANDATE

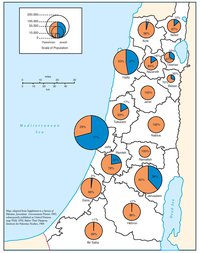

THE DEMOGRAPHY OF PALESTINE, 1931

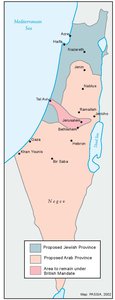

THE PEEL COMMISSION PARTITION PROPOSAL, 1937

THE WOODHEAD COMMISSION PARTITION PROPOSALS, 1938

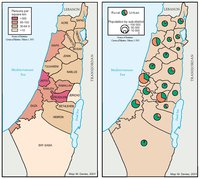

PALESTINIAN AND ZIONIST LANDOWNERSHIP BY SUB-DISTRICT, 1945

THE MORRISON-GRADY PARTITIONED TRUSTEESHIP PLAN, 1946

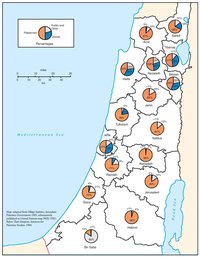

POPULATION OF PALESTINE BY SUB-DISTRICT, 1946

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE, 1948

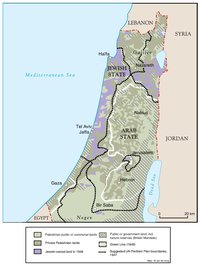

THE UNGA PARTITION PLAN, 1947 – THE 1948 WAR & THE 1949 ARMISTICE LINES

POPULATION MOVEMENTS, 1948-1951

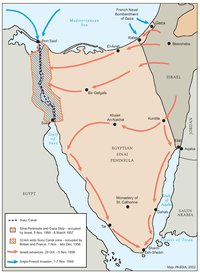

THE SUEZ WAR, 1956

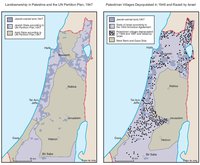

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE AND THE UN PARTITION PLAN - PALESTINIAN DEPOPULATED AND DESTROYED VILLAGES, 1948-1949

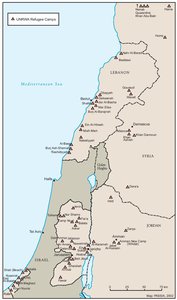

THE PALESTINIAN DIASPORA, 1958

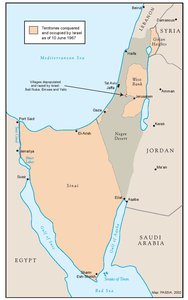

THE NEAR EAST AFTER THE JUNE 1967 WAR

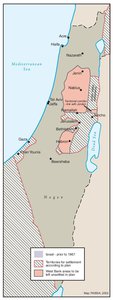

THE ALLON PLAN, JUNE 1967

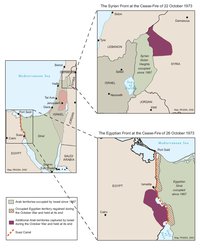

THE OCTOBER WAR, 1973

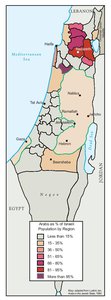

THE PALESTINIANS INSIDE ISRAEL, 1977

THE CAMP DAVID ACCORDS, 1978-1979

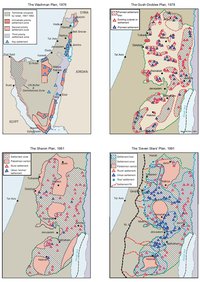

ISRAELI SETTLEMENT MASTER PLANS, 1976-1991

THE 1991 MADRID PEACE CONFERENCE & ISRAELI SETTLEMENTS

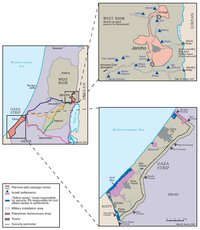

GAZA-JERICHO (OSLO I) AGREEMENT, CAIRO, 4 MAY 1994

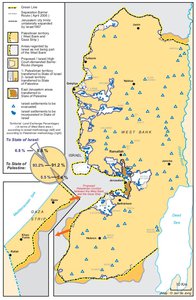

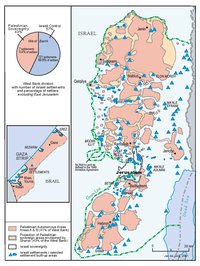

INTERIM (OSLO II) AGREEMENT, TABA, 28 SEPTEMBER 1995

WYE RIVER MEMORANDUM, 23 OCTOBER 1998

SHARM ESH-SHEIKH AGREEMENT, 4 SEPTEMBER 1999

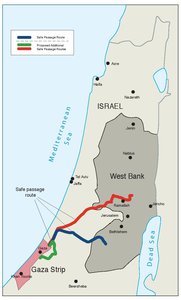

PROTOCOL CONCERNING SAFE PASSAGE BETWEEN THE WEST BANK AND THE GAZA STRIP, 5 OCTOBER 1999

GAZA, 2000

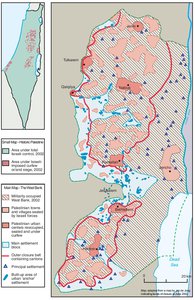

WEST BANK AND GAZA STRIP, MARCH 2000

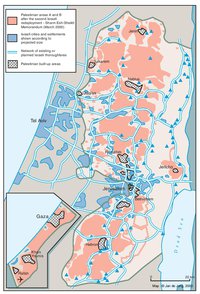

CAMP DAVID PROJECTION, JULY 2000

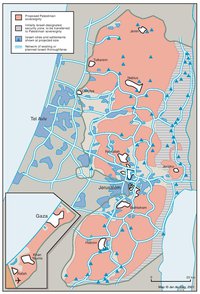

TABA TALKS PROJECTION, JANUARY 2001

THE SHARON PROPOSAL, SPRING 2001

THE REINVASION OF THE PALESTINIAN TERRITORIES, 2001-2002

THE ROAD MAP, 2003

THE GENEVA INITIATIVE AND ACCORD, 2003

THE ISRAELI DISENGAGEMENT PLAN, 2003-2005

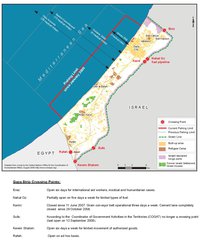

AGREED DOCUMENTS ON MOVEMENT AND ACCESS FROM AND TO GAZA, 2005

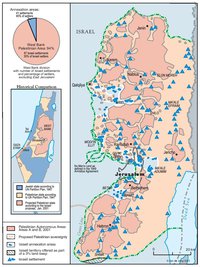

THE SETTLERS' PLAN FOR PALESTINIAN AUTONOMY, 2006

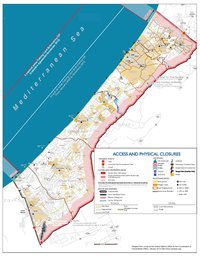

THE GAZA STRIP TODAY (2014)

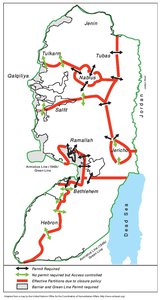

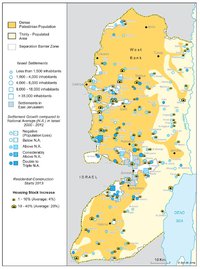

THE WEST BANK TODAY (2014)

ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES

HEBRON

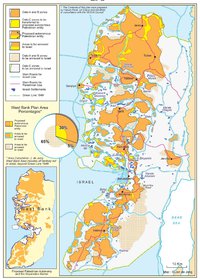

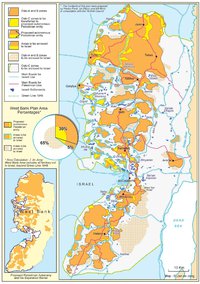

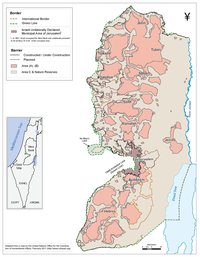

Area C